Death in London

4 December

This will surely be my final trip to London for this year and it will be my sixth.

It has been a long while since I was back and forth so often.

Once we'd deposited our bags in the Civil Service Club, Roland suggested that we grab a quick Chinese meal at the Canton Restaurant, one of his favourite haunts of yesteryear, positioned behind Charing Cross Road on the fringes of Chinatown. It was one of those times when the passage of the years and probably a change of ownership had turned a pleasant venue into a great disappointment. We ate up and left.

Once we'd deposited our bags in the Civil Service Club, Roland suggested that we grab a quick Chinese meal at the Canton Restaurant, one of his favourite haunts of yesteryear, positioned behind Charing Cross Road on the fringes of Chinatown. It was one of those times when the passage of the years and probably a change of ownership had turned a pleasant venue into a great disappointment. We ate up and left.

The main purpose of our coming to London was to attend a performance of David McVicar's new production of Britten's Death in Venice. Initially, it was to have been Mark Elder conducting but ill-health prevented him seeing the project through and Richard Farnes took over - a choice heartily seconded by Roland and I having witnessed his work with Opera North including Peter Grimes.

The main purpose of our coming to London was to attend a performance of David McVicar's new production of Britten's Death in Venice. Initially, it was to have been Mark Elder conducting but ill-health prevented him seeing the project through and Richard Farnes took over - a choice heartily seconded by Roland and I having witnessed his work with Opera North including Peter Grimes.

We were not disappointed.

This was the sixth or seventh presentation of this work that I've attended since 1973 and I'm still entranced by the wonderful mystery in the orchestra and, in particular, the Gamelan sounds.

Mark Padmore's Aschenbach was as good vocally as any that I have heard since Pears in 1973 at the Edinburgh Festival and I think that his acting was more interior and less signalled than his predecessor. Whilst lavish, the production was not bloated and kept the sweep of the narrative pressing forward. Gerald Finley was stonkingly good in the multiple nemesis roles and Tim Mead's counter-tenor for the Voice of Apollo rang out.

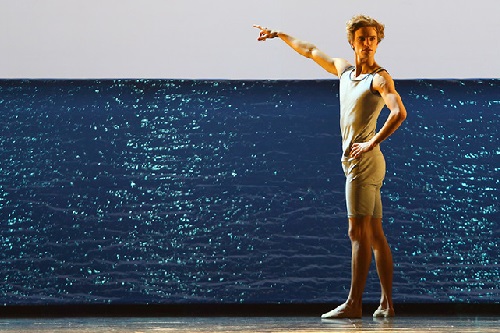

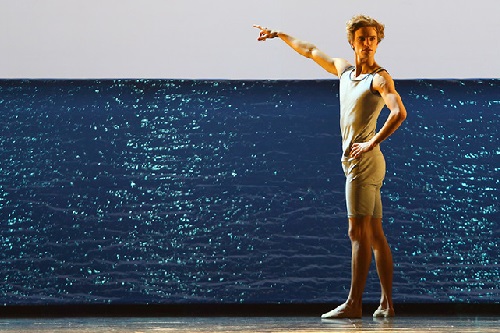

One of the elements which sorts this work out is how to deal with the balletic Poles including Tadzio.

One of the elements which sorts this work out is how to deal with the balletic Poles including Tadzio.

Leo Dixon was ideally cast visually - light and lithe without being too muscular or too fey.

The choreography also was kept descriptive and classically based and so did not stand apart from the rest of the presentation.

In 1973, Robert Hugenin was daringly impressive for the times but he possessed a somewhat upholstered posterior which took a second or so to stop jiggling whenever he adopted a position. It was eye-catching for most of the wrong reasons. And, even to my untrained 19-year-old's eyes, Ashton's choreography was limp and nelly and, very surprisingly in retrospect, not good on differentiating the boys into separate characters.

By the end, Roland and I had both had our withers rung and so we decamped to the The Ship & Shovell on Craven Passage for a drink before bedtime.

By the end, Roland and I had both had our withers rung and so we decamped to the The Ship & Shovell on Craven Passage for a drink before bedtime.

Coming back, I thought a photo opportunity of me in Trafalgar Square over fifty years since I was first there would be a good thing.

Coming back, I thought a photo opportunity of me in Trafalgar Square over fifty years since I was first there would be a good thing.

Our main objective for the second day in London was Tate Britain. However, in walking down Whitehall, we encountered the Banqueting House and I mentioned to Roland that I had never been inside. Well, that was enough for him. We checked that it was open, bought our tickets and made our way upstairs.

It really is a splendid piece of historic civic architecture and design, even leaving aside the fact that Charles I spent his last mortal hours on earth in this room before stepping through a window and onto a platform so as to be executed.

Blood on the pavement aside, I was totally bowled over by the epic qualities of Rubens' ceiling paintings. I could have lain back on one of the big squidgy cushions and stared upwards for the rest of the morning.

As we walked on I took some photos of the Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey. These are not the angles we normally see and they reminded me of how the Hungarian Parliament Buildings in Budapest drew inspiration from our mid-nineteenth century architects and how Westminster Abbey would have drawn heavily on French influences in its design.

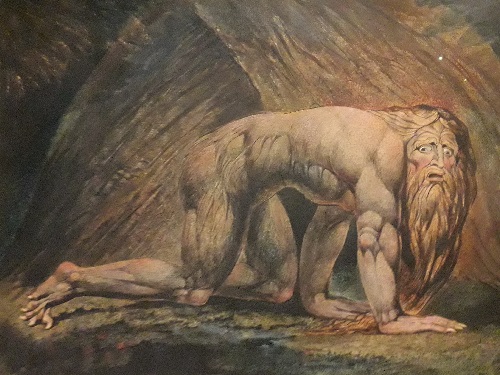

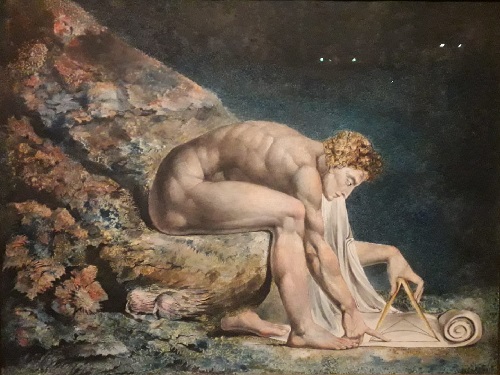

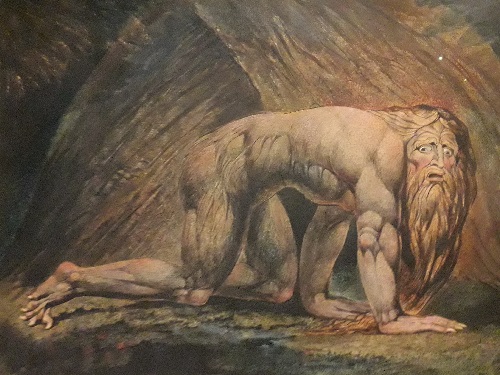

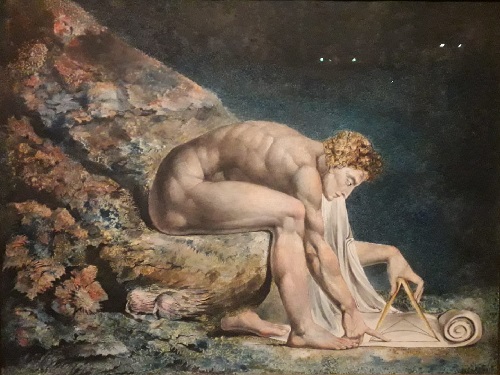

I have loved William Blake's combination of poetry and graphical art since I first encountered it in my later teens. Some of the tub-thumping polemics stirred my young soul and the knowledge that his were the words to the great socialist hymn Jerusalem simply confirmed my opinion that he was in the pantheon of the greats.

I have loved William Blake's combination of poetry and graphical art since I first encountered it in my later teens. Some of the tub-thumping polemics stirred my young soul and the knowledge that his were the words to the great socialist hymn Jerusalem simply confirmed my opinion that he was in the pantheon of the greats.

I may retreat slightly from that view in my later years seeing him as, amongst other things, somewhat crazed. Nevertheless, you've got to hand it to the man that he worked through a number of great technical innovations in the fields of printing and etching and that, working in a period of political terror and oppression, he showed great courage in promoting his political vision of intellectual freedom.

What the exhibition did remind me, however, was that a little Blake goes a long way. And that so many of the printed books like Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience are so small that only one person at a time can comfortably view them.

But, if you are going to have a legacy, then Nebuchadnezzar and Newton will do very nicely.

Once we'd deposited our bags in the Civil Service Club, Roland suggested that we grab a quick Chinese meal at the Canton Restaurant, one of his favourite haunts of yesteryear, positioned behind Charing Cross Road on the fringes of Chinatown. It was one of those times when the passage of the years and probably a change of ownership had turned a pleasant venue into a great disappointment. We ate up and left.

Once we'd deposited our bags in the Civil Service Club, Roland suggested that we grab a quick Chinese meal at the Canton Restaurant, one of his favourite haunts of yesteryear, positioned behind Charing Cross Road on the fringes of Chinatown. It was one of those times when the passage of the years and probably a change of ownership had turned a pleasant venue into a great disappointment. We ate up and left.

The main purpose of our coming to London was to attend a performance of David McVicar's new production of Britten's Death in Venice. Initially, it was to have been Mark Elder conducting but ill-health prevented him seeing the project through and Richard Farnes took over - a choice heartily seconded by Roland and I having witnessed his work with Opera North including

The main purpose of our coming to London was to attend a performance of David McVicar's new production of Britten's Death in Venice. Initially, it was to have been Mark Elder conducting but ill-health prevented him seeing the project through and Richard Farnes took over - a choice heartily seconded by Roland and I having witnessed his work with Opera North including  One of the elements which sorts this work out is how to deal with the balletic Poles including Tadzio.

One of the elements which sorts this work out is how to deal with the balletic Poles including Tadzio.

By the end, Roland and I had both had our withers rung and so we decamped to the The Ship & Shovell on Craven Passage for a drink before bedtime.

By the end, Roland and I had both had our withers rung and so we decamped to the The Ship & Shovell on Craven Passage for a drink before bedtime.

Coming back, I thought a photo opportunity of me in Trafalgar Square over fifty years since I was first there would be a good thing.

Coming back, I thought a photo opportunity of me in Trafalgar Square over fifty years since I was first there would be a good thing.

I have loved William Blake's combination of poetry and graphical art since I first encountered it in my later teens. Some of the tub-thumping polemics stirred my young soul and the knowledge that his were the words to the great socialist hymn Jerusalem simply confirmed my opinion that he was in the pantheon of the greats.

I have loved William Blake's combination of poetry and graphical art since I first encountered it in my later teens. Some of the tub-thumping polemics stirred my young soul and the knowledge that his were the words to the great socialist hymn Jerusalem simply confirmed my opinion that he was in the pantheon of the greats.