Back in Liverpool, the contents of the exhibition are now on show at the Walker Art Gallery under the title Victorian Treasures. I went to see it and bought a catalogue - it was in Japanese.

Back in Liverpool, the contents of the exhibition are now on show at the Walker Art Gallery under the title Victorian Treasures. I went to see it and bought a catalogue - it was in Japanese.

The collection of paintings bought by wealthy Liverpool-based merchants and industrialists who were also patrons of the arts forms the basis of displays in Merseyside galleries which are part of the treasures of this region.

Recently, during the closure of some galleries whilst renovation and re-decoration took place, the Walker Art Gallery had the opportunity to bring together a substantial selection of Victorian paintings and watercolours from the entire art collections of National Museums Liverpool and offer them as a major blockbuster exhibition in Japan. I have no idea how much of a gamble the idea seemed at the offset of the project but word is that the exhibition was hugely popular in Japan touring four major cities during 2015 and 2016 with over 150,000 visitors attending.

Back in Liverpool, the contents of the exhibition are now on show at the Walker Art Gallery under the title Victorian Treasures. I went to see it and bought a catalogue - it was in Japanese.

Back in Liverpool, the contents of the exhibition are now on show at the Walker Art Gallery under the title Victorian Treasures. I went to see it and bought a catalogue - it was in Japanese.

With well over fifty items on view, it was a substantial exhibition for Liverpool.

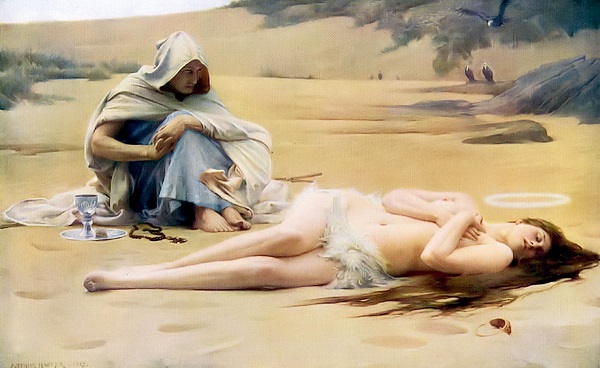

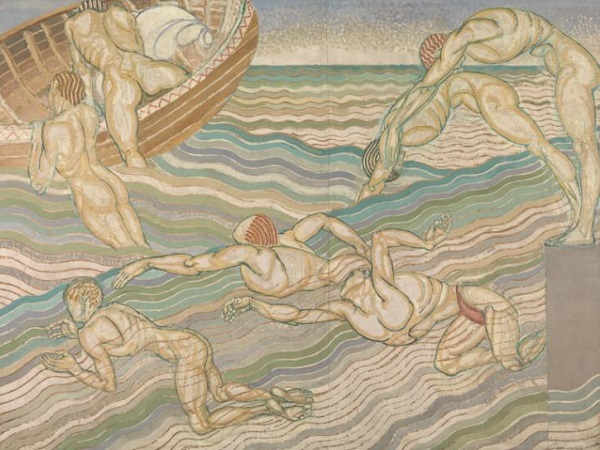

I guess that there were two distinct threads running through the offering. Firstly there were the established, classical artists such as Frederic Leighton (his Perseus and Andromeda is on the right), Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Edward John Poynter.

Then there were the pioneering Pre-Raphaelite artists which included the likes of John Everett Millais (his Sir Isumbras at the Ford is immediately below), Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt.

Looking at the selection as a whole, although there were contemporary scenes painted with an eye to the social interactions of the day, most of the content was inspired by biblical, legendary or mythological subjects. And much of the presentation was dramatic capturing a moment within an ongoing narrative. And there was often a cinematic verve to the draughtsmanship of the composition (I give you Leighton's Perseus and Andromeda above).

The (exclusively male) artists certainly understood their customer base and knew how to flatter and titillate their (predominantly male) buyers and viewers. Discrete and tasteful nudity such as might engage the intellect (not to mention the instincts) of an "understanding connoisseur" was positively de rigueur. Here, in Arthur Hacker's Pelagia and Philammon, you have a scene from Charles Kingsley's racy novel 1853 novel Hypatia where the monk Philammon blesses his half-sister Pelagia before her burial in the desert (there is a complicated backstory which need not bother us here).

In the novel, Kingsley apparently says of Pelagia that "her clothes had failed her" (now there's a phrase that is likely to stiffen the cock of any young Victorian gentleman). Hacker must needs be more discrete as he is providing the visuals rather than summoning the visuals up through evocative language. So, he provides Pelagia with some (virginally white) woolly draping over her middle areas and places her arms and hands clasped over her breasts - the connoisseur will use his imagination to understand that which is covered.

During my adolescence, I found that I was far more drawn to John William Waterhouse's Echo and Narcissus. I wasn't particularly concerned with Echo's pert tits. However, the languorous pose that Narcissus had adopted drew my attention in a way that should have certainly alerted my fourteen year old self to the true nature of my sexual orientation (except that, in 1968, there wasn't the language or the permissions or the social acceptance that would have allowed me to travel down the road of such externalised self-knowledge at that early stage of my life).

At some point, I remember realising that the diagonal line of the youth's left leg led up to an apex which must have been the sitter's unclothed left buttock. And then (I don't remember if it was the same or a subsequent occasion), I remember thinking that, if the whole painting were to be revolved through 180°, I would be able to see right up that beautiful young man's arse. And that was the moment when, for the first time in my post-pubescent life, I experienced the uncomfortable social embarrassment of realising that I was sporting a healthy boner in a public place.

Anyhow, we have digressed. I enjoyed the exhibition enormously.

The availability of publicly funded theatre through cinecasts is one of the treasures of current social life. Both the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company do excellent work in this regard and I feel very blessed to be able to sample their work without the hassle of being present in London or Stratford-upon-Avon.

I hadn't seen Julius Caesar for a very long time and so I was looking forward to the RSC's new production in a cinecast at my local Odeon Cinema. However, availability is no guarantee of quality and so, as in life, it is accepted that the rough must be taken with the smooth.

I hadn't seen Julius Caesar for a very long time and so I was looking forward to the RSC's new production in a cinecast at my local Odeon Cinema. However, availability is no guarantee of quality and so, as in life, it is accepted that the rough must be taken with the smooth.

The verse speaking was as ploddingly leaden as an AmDram production with great pauses letting any sense of pace drag lamentably. There was no sense of physical danger or fear and the acting among the throng would have disgraced Up Pompeii!.

Less than average does not begin to sum it up really.

The Brutus/Cassius relationship was probably the most interesting part of it. But I did think that all that incessant manly arm clasping and kissing kept slowing things down.

I think for the play to work you have to have a Caesar who is feared enough for people to want to get rid of him. Then you get the political momentum to rocket the plot forward.

There are, after all, three coups d'état during the course of the evening. Octavius/Anthony replace Brutus/Cassius. Brutus/Cassius replace Julius Caesar. But (and this is the whole point of the first scene which went for nothing in this production) Julius Caesar replaces Pompey. And, once you have anarchy, only anarchy can follow until order is restored. It is a theme that runs through Shakespeare's English History Plays and which stirred the Elizabethan and Jacobean minds. The peaceful transition of power is an important element which marks a successful state from a rogue state.

I took a leap of faith and travelled to London, there and back in a day, to enjoy some treasures in the capital.

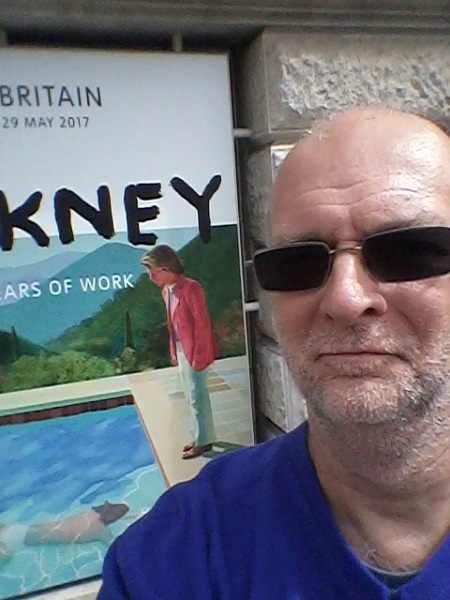

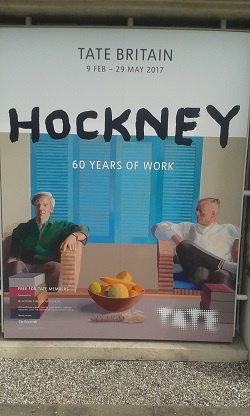

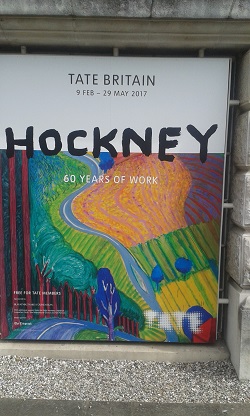

I was a bit excited to be seeing this David Hockney exhibition at Tate Britain.

I was a bit excited to be seeing this David Hockney exhibition at Tate Britain.

It turned out to be a delightful exhibition.

There were so many images that have been a soundtrack to my adult life.

There were so many images that have been a counterpoint to my adult life.

Such painterly skill and draughtsmanship.

And such glory!

Such celebration!

Such COLOUR!!!

I also attended the Queer British Art exhibition which marked fifty years since the Woolfenden Bill was passed into law. I found this interesting but, for me anyway, hardly revelatory. And, by ending the story at 1967, hardly celebratory either.

I also suspect that, by concentrating on the establishment figure, such as John Singer Sargent, Dora Carrington, Duncan Grant and David Hockney, there were swathes of art works by less well known queer artists who were simply ignored. And I also suspect that some of these figures would have enlivened the exhibition with works which were lively, transgressive, celebratory, etc, etc, etc giving a more rounded portrait of an era of queer outlaws.

I had a nom nom Salt Beef Special lunch at my regular haunt of Gaby's Deli which is a gastronomic treasure.

And then I went to the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden for the prompting reason for travelling to London, there and back in a day. I finally got to see a live performance of Kenneth MacMillan's Mayerling.

I can remember the responses to the first round of performances back in 1978 and how it was hailed as being something very new and challenging with subject matter that was complex and adult.

There was a section of about fifteen minutes shortly before the double suicide at the end which I thought was riveting. Otherwise, ultimately, I found it something of a disappointment. Having your male lead clutch at a skull may have seemed incredibly riské and profound to the professional balletomane back in the late 70s but today, in 2017, I just went "So what?" And I suspect that I would have felt the same in 1978 as well.

So, box ticked but further exploration unlikely.

By 21:15, I was home again enjoying a nice cup of tea in my jim jams. It was an eventful and ultimately satisfying day filled with treasures which I shall hold dear to my heart but not the sort of schedule that I should like to pursue on a regular basis any longer.